Colorado River Water Crisis

Author: James Mattil

The Colorado River Water Crisis, of which the public knows very little and water users and politicians like it that way, as they always have.

The American Southwest is a popular desert region to visit and live, with diverse, world-class recreational opportunities and one nagging, controversial problem – Water. As scarce as water is, it’s the driving force behind nature’s most impressive creations. Its incredible erosive power carved the Grand Canyon, Canyonlands, Escalante Staircase and many other geological features that define the Southwest. And we know to carry plenty of water when hiking or traveling these arid lands. But most of us know little about the water crisis that threatens the precious rivers, regional agriculture and population growth.

The Southwest is experiencing a long and severe drought, certainly cyclical and probably as a result of global climate change. Snowpack in the Rockies has been diminishing and rainfall declining, leaving the land dry and water reservoirs approaching crisis level. The Colorado River no longer flows to the sea, the Gila River no longer flows into the Colorado and, as Will Rogers once said, “the Rio Grande is the only river I ever saw that needed irrigation.” Even so, new homes, businesses and highways remain the regions most plentiful crops, as they spring from the desert regardless of weather conditions.

Background:

Where does the water come from to provide life support for growing populations…and when will it run out?

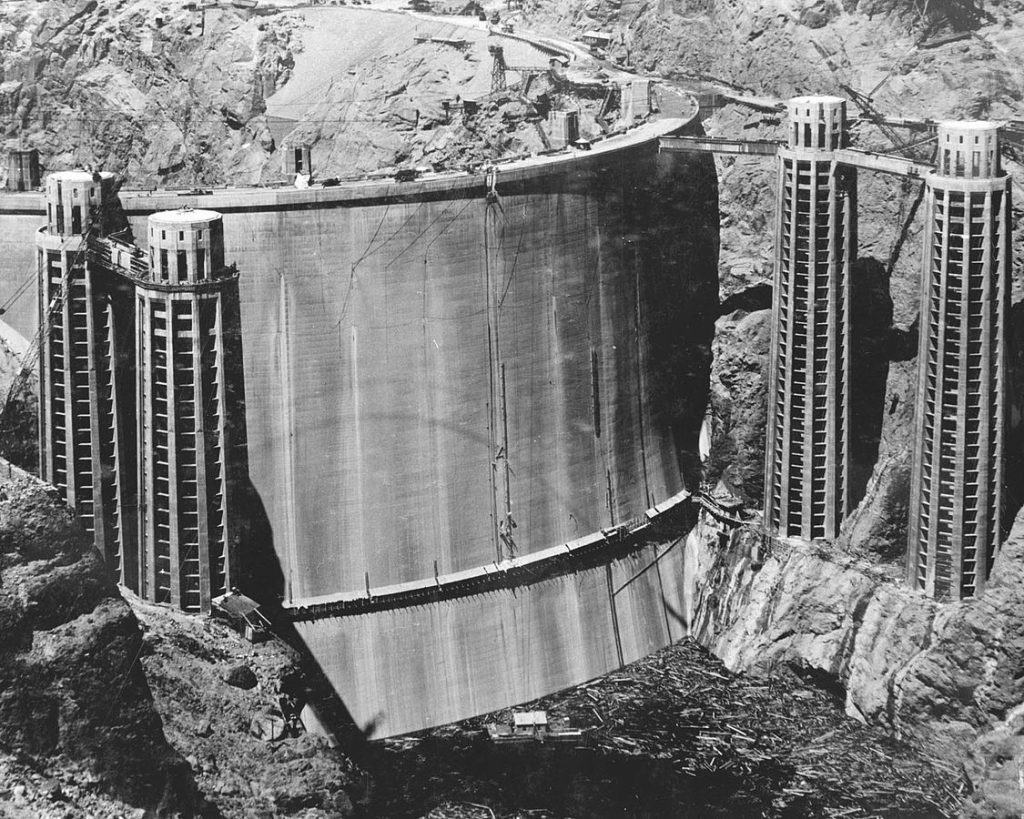

The Colorado River flows 1,450 miles from its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California, or at least it used to. The river provides life support to over 40 million people. For the past 16+ years, the river has dried up before reaching the sea. And for the past 30-years no water has has flowed through the Hoover Dam spillway, due to the low water level.

Today, the West is in a prolonged state of drought, nearing the crisis point, with no end in sight. Colorado River water flows is at its lowest level in the past 1,000 years. But the Southwest Water Crisis transcends the current drought and even climate change. The problem is surprisingly simple:

Fact: A limited supply of water cannot support an unlimited amount of development.

Hence, it’s no surprise to learn that there’s a water crisis in the arid Southwest. What is surprising is that few people talk about it and nobody is doing anything to fix it.

Meanwhile, cities continue their unrelenting growth and sprawl in the desert, while agriculture remains, by far, the largest water consumer. Sure, there are rivers, but that water is already allocated under the 1922 Colorado River Compact, which over-estimated the water flow in the first place. Today, nearly 100-years later we’re facing the truth. There is no more water and there is none is in the weather forecast. And yet today, seven states and over 40-million people rely on water from the Colorado River.

The Colorado River Compact of 1922

In 1912, New Mexico and Arizona became states and in 1913, Los Angeles began diverting water from the Owens Lake in the Eastern Sierra through the 225-mile Los Angeles Aqueduct. By 1926 Owens Lake was dry and the once-lush Owens Valley was doomed to decay. Since

then, Los Angeles and California’s thirst for water has continued unabated and plays an important role in the controversies over Western Water Law.

In 1922, Congress adopted the Colorado River Compact which estimated the water supply and allocated water rights on a first-come, first-serve basis. Whoever first put the river water to beneficial use was granted the right to such water in perpetuity, known as the doctrine of “prior appropriation.” These foundations include such enlightened concepts as The Rule of Priority (“First in time, first in right”) and the Beneficial Use Requirement (“Use it or lose it”), which encourages wasteful use. This was known as the Law of the River, and it remains in effect today.

Back in 1922, few imagined the population growth to come. The Compact was between four Colorado River Upper Basin states including: Wyoming, Colorado, Utah and New Mexico; and three Lower Basin states of California, Arizona and Nevada. The dividing point between the Upper and Lower river runs through Lee’s Ferry just below the Glen Canyon Dam in Page, AZ and just upstream of Marble Canyon, gateway to the Grand Canyon.

This deal was made in 1922, long before public comments and long-term public interests were considered necessary. And the negotiations were clouded in corruption. That was then and today little has changed.

The Compact immediately over-estimated annual water flow at 17 million acre feet (AF) and allocated half the water to Upper Basin states and half to Lower Basin states (7.5 million acre feet (AF) each), plus 1.5 million AF was allocated to Mexico. More recent flow estimates put the water supply at about 13 million AF, or less, so we can see a big problem from the git-go.

The 1922 Colorado River Compact allocated water to the nearby states as follows:

Upper Basin (7.5 million acre-feet (MAF) annually)

Arizona 0.05 MAF 0.70%

Colorado 3.86 MAF 51.75%

New Mexico 0.84 MAF 11.25%

Utah 1.71 MAF 23.00%

Wyoming 1.04 MAF 14.00%

Lower Basin (7.5 million acre feet annually)

Arizona 2.80 MAF 37.30%

California 4.40 MAF 58.70%

Nevada 0.30 MAF 4.00%

IN 1944, Mexico was allocated 1.50 MAF annually, BUT none of the prior allocations were reduced. It was simply decided to add 1.5 MAF of supply that didn’t exist.

Colorado River Water Supply

The story of the Colorado River is pretty simple; it conforms to the law of supply and demand – with one major exception. In economics the differences between supply and demand affect price. Not so with the Law of the River, where politics, power and even corruption decide the price of water.

There are 15 dams along the main stem of the Colorado and many more on its tributaries. To simplify matters, we’ll look at a select group of major dams and their reservoirs, including:

Glen Canyon Dam -1966 (Lake Powell);

Hoover Dam -1936 (Lake Mead);

Davis Dam -1951 (Lake Mohave);

Parker Dam -1938 (Lake Havasu) and

Imperial Dam -1938 (Imperial Reservoir)

an

The Salton Sea -the river’s “dead pool”

What is the annual average river flow?

One would think that this would be known with precision, but one would be wrong. It’s said that water flow in the Colorado River has averaged 15.34 million acre-feet annually over the past 10 years. A “water year” (WY) runs from Oct. 1 through Sept. 30. Water is collected behind the dams to help control flooding, generate electricity and for life support and agriculture. The Compact allocates 15-million AF to the various states and their water users.

Nature’s Revenge

However, a large amount of water evaporates from the lakes in the hot, dry desert. An elusive amount of water also seeps into the ground beneath the lakes. And sediment collects on the lake bottoms, which artificially raises the water level reducing the amount of water we think is stored in the reservoirs, and this grows over time.

It’s estimated that these losses reduce the estimated water flow by about 1.5 – 2.5 million acre-feet annually, leaving just 13-14 million AF to meet the water allocations totaling 16.5-million AF

(See table below). Evaporation loss has been estimated at over 1.1-million AF/yr.

Lake Mead capacity is 30,944,400 AF (1935). By 1948 sedimentation amounted to a loss of 1,066,400 AF and by 1963 reached 2,623,100 AF. However, Glen Canyon Dam has since intercepted much of the sediment, reducing build-up in Lake Mead (but increasing build-up in

Lake Powell). There have been no further estimates at Lake Mead. There are no available estimates of sedimentation in Lake Powell, although the Colorado River deposits an estimated 45 million tons of sediment annually.

Hence, it seems fair to say that sediment formerly deposited in Lake Mead, now accumulates in Lake Powell at a similar rate and thus reduces water “capacity” accordingly. As a result, evaporation reduces water “supply” by 1.1 million AF and sedimentation has reduced reservoir capacity by some unknown amount, greater than 3.5-million AF.

Note: These kind of apples-to-oranges data seem inexplicable unless intended to obscure the results desired.

Colorado River Water Demand

Western states have the highest water consumption per capita, so, there’s certainly room for improvement. However, life support represents only about 23% of water use; the other 77% goes into agriculture (in the desert!) And this is where the water data gets muddied.

Let’s try to discover where the water goes and where it ends up. We know it no longer flows back to the sea.

The 1922 Colorado River Compact apportioned 7.5 million acre-feet of river water annually to the Upper Basin and another 7.5 million acre-feet annually to the Lower Basin. Upper Basin water use is generally lower than the allocation. There are few large cities and relatively limited agricultural demands. However, this is beginning to change in states like Colorado who have plans to divert their water allocation eastward of the Continental Divid to support development along the eastern Front Range.

Hence, it is the Lower Basin that uses most of the water, The Lower Basin’s 7.5 million acre-feet was further apportioned by the Boulder Canyon Project Act to the Lower Division States as follows:

- 4.4 million acre-feet to California,

- 2.8 million acre-feet to Arizona,

- 300,000 acre-feet to Nevada.

Later, the Mexican Water Treaty of 1944 recognized the United States’ obligation to annually deliver 1.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water to Mexico.

(One acre-foot is equal to approximately 326,000 gallons)

Note: No water was ever allocated to the Pacific Ocean and Gulf of California. Hence, no water is left to flow into the ocean and recharge the water cycle, and Mexico’s allocation as simply added, without any corresponding reductions elsewhere. And the river’s flow has been over-estimated from the beginning.

Colorado River Water Users

In Arizona and California, Colorado River water is used for agricultural irrigation and domestic uses. In Nevada, the water is only used for domestic purposes.

The use of Colorado River water in the Lower Basin is governed by the Boulder Canyon Project Act. Section 5 of the Act refers to the contract requirement for Colorado River water; therefore, the contracts with the Secretary of Interior are referred to as “section 5 contracts.”

In these section 5 contracts, “irrigation use” means the use of mainstream water for the commercial production of agricultural crops or livestock, including use of water for other purposes related to agricultural activities on tracts of arable land greater than 5 acres.

“Domestic use” means the use of water for household, stock, municipal, mining, industrial, and other similar purposes, but excludes the release of water solely for generation of hydroelectric power.

There is a long list of water entitlements that reflect years of controversy, negotiation and horse-trading of allotments and the inevitable corruption.

Colorado River Water Winners & Losers

Obviously, there is a controversial power struggle between urban and rural (agricultural) needs. The vast majority of water currently goes to desert agriculture in California and Arizona. But, because money is power, when push comes to shove, urban interests are most likely to prevail. The fact is that most of the desert agriculture is devoted to crops with very high water demands, which is hard to justify. Many such crops are already grown in Mexico and elsewhere.

However, there is a third voice – a silent voice – that has been ignored since the Compact was adopted in 1922 – Nature. Today, Nature does have a voice; it’s the voice of the people, who are concerned for the environment, the river, the fish, the wildlife, the land and the climate.

But this voice is not heard behind the closed doors of the water commissions, water user associations, the Bureau of Reclamation, the Dep’t of the Interior, or in the Media.

Few people realize that environmentalists stopped proposed plans to dam and flood the Grand Canyon. Fewer still are aware of a plan to recycle river flow to convert Hoover Dam into a battery. And little is know about the connection between southwestern power plants built for the sole purpose of pumping water across mountains to support dubious projects that were not economically feasible unless subsidized by taxpayers.

It’s time to bring water policy into the daylight and craft a new Compact that is appropriate for today and our uncertain future. It’s time to address the question: how will Climate Change impact the western rivers and the populations that rely on those rivers for water.

Cadillac Desert (The Movie)

Additional Information Resources:

Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water (book)

by Marc Reisner